Change in Google's peering policy

In the last few months, there’s been a constant discussion around Google’s change of peering policy. This has been across various ISP groups, NOG meetings etc. For those who may not know - Google has gone from “Open peering policy” into a “Selective peering policy” sometimes between 14 Feb 2025 - 06 Mar 2025.

This initially started as Google stop peering over the IXPs and that actually made technical sense. Later more & more ISPs, content players started complaining about Google being closed on the peering front by either not responding, delaying and in some rare cases even rejecting peering requests. Today Dr. Peering on X pointed to Google’s presentation at NANOG 94 about the change in the peering policy.

Dave Schwartz from Google explaining Google’s peering policy and Verified Peering Provider (VPP) program at #NANOG94. Found via LinkedIn, video here … https://t.co/EGEVAR6MJc pic.twitter.com/z0suA2wlFJ

— Dr. Peering (@DrPeering) July 1, 2025

This is interesting as finally there’s an official presentation by Dave Schwartz on some of the challenges they had and what triggered them in this direction.

What has changed

- Google is not going to do bilateral peering over an IXP with any new network.

- They prefer 100G PNIs with networks with at least 10G traffic (Google -> Other network direction, peak 10G flow).

- For everyone who doesn’t fit into the 100G port model, they suggest coming via VPP which is simply a certification from Google that the given network is peered to them with different grades of redundancy (as defined by silver Vs gold status) or respective upstream IP transit provider.

- Google will not deploy (expensive) YouTube edge at smaller peering locations anymore.

Some quick points around why Google is not openly anymore

- Ten years ago (2015) they were expanding, traffic flows were unpredictable and they needed a massive amount of bandwidth. In that mix, peering made sense (besides many other things). Now in 2025, traffic growth is predictable, they already have a massive amount of peering with many players and (my guess) the peering situation of AS15169 is reaching a diminishing return.

- Google Cloud is now at the centre of everything - from investment to growth, from product to AI adoption. Essentially more peering with lower capacities is causing them planning issues as explained in slides 6 & 7. Running a small 10G port at an IX or even doing remote peering with a small transport wavelength can get parts of their edge congested at times.

- Their network expansion is driven by Google Cloud & not by YouTube anymore.

- Many of their Cloud customers are running VPN concentrators in Google Cloud and expect stable latency. They seem to be having transport challenges within the metro during (planned/unplanned) outages as well as random traffic spikes.

- They are pushing layer 2 IXPs to become layer 3 partial transit providers by enrolling in VPP.

Does it make technical sense?

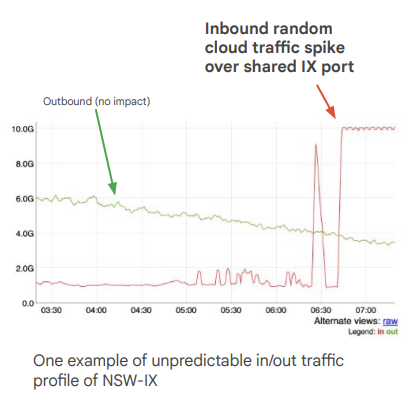

Things which he said technically make sense if we see them in isolation. But if we see the internet at large, many of those things are questionable. Take e.g his latency spike case from NSW-IX (New South Wales Internet Exchange):

Surely Google can get edge port congested if they run a 10G port at an IX with at least 24 participants with over 100G capacity, 7 players with 40G and many players with 10G ports. It’s unclear from Dave’s presentation when this issue occurred but even if I check now their port size is just 20G at this IXP. If they simply do not add any new peers anymore - a congestion issue can still come from existing peers, especially from the internal transport network of their large peers which maintain a backbone.

Why layer 2 peering was better than transit or even partial transit/layer 3 peering in the first place? That is because if we take a 100G wavelength or run 100G over dark fibre to Google, we know for sure that capacity exists and can be used. If I try to do the same via another layer 3 network in between (or even an MPLS circuit), there is no guarantee of the capacities involved. The link might be over an oversold transport.

Technically VPP is simply “offloading congestion problem” to someone else (large to mid-sized networks).

Commercial angle

Ultimately there’s a clear commercial angle to these decisions. Dave hints at that in his talk multiple times. From hints as well as from what we know from public data:

- Cloud and AI growth needs massive networking resources in terms of engineering manpower, hardware, datacenter capacity etc and Google is trying to divert some of that from its peering ecosystem. Remember AI needs massive bandwidth within DC and super tiny with the internet-facing edge.

- The cost of borrowing money in the US has gone up significantly. 2015 was the time when everyone from Google to CDN players like Akamai/Fastly and many more were expanding fast. Money was “cheap” and hence many things were possible back then but not anymore.

- While Google may not be technically a tier 1 transit-free network, for all practical reasons it is. Their traffic volume numbers are not known but I would guess a super-tiny part of their traffic goes via their transit. Thus whether they peer with a smaller network or not, it has virtually no impact on their transit traffic. Only their traffic volume with the dominant incumbent would increase in that market.

- The cost of IP transit, peering, and hardware has declined over time but the cost of manpower has gone crazy. I am writing this post when just 5 days ago Meta hired three OpenAI researchers with bonuses of as high as $100 million. For Google spending $300k - $500k on engineers, the manpower cost is just huge compared to the money going on the other aspects of the network including peering.

- More and more traffic is getting concentrated over the years. Take e.g my home country India - Jio & Airtel have massive eyeballs. Google’s traffic once we exclude Airtel/Jio and a few other PNIs, is likely a low single-digit percentage. I can imagine it won’t be very different in many countries around the world with a very high concentration of eyeballs on a limited set of players. Imagine traffic in the US once you exclude AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile. Comcast & a dozen more networks which already have the PNI.

So ultimately it will degrade things for a small set of networks (and their users) and it’s a calculated loss Google has decided to take with this strategic shift in peering. Many of us have seen a vibrant IXP ecosystem develop because of Google’s aggressive peering push. An interesting note 2015-2016 was such a crazy growth time that Mr Geoff Huston (Scientist at APNIC and my good friend) even declared “death of transit”.

Disclaimer:

This is my personal blog and hence posts made here are in my personal capacity.

These do not represent the views of my employer.